In a fragmented world, where grand narratives have given way to disjointed perspectives and fractured contexts, expectations are no longer forecasts. They are emergent properties: elements of reality that arise from observing patterns, cross-reading signals, and the convergence of distant and even opposing practices. We call them extra-large expectations because they transcend traditional boundaries, geographic, generational, and disciplinary, and become tools for navigating complexity.

In the realm of intelligence, this emergent expectation is perhaps the most problematic. There is no more overused topic today than artificial intelligence. That is why we do not want to approach AI as an alien mind competing with humans, but as a network of agencies, human and non-human, interacting with one another. This booklet is an invitation to step away from the race for benchmarks, endlessly chasing the title of the best AI, and to anchor ourselves instead to real problems that we, as people and organizations, can address in hybrid, collaborative, and situated ways.

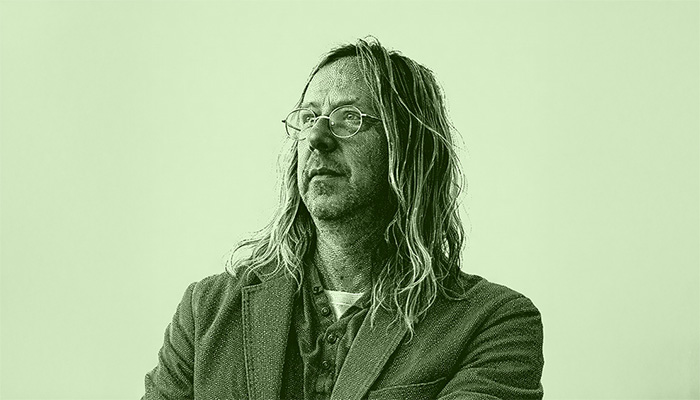

“Build your own benchmark,” argues Ethan Mollick, one of the most respected, and most pragmatic, experts on generative AI in organizations. But let us take a step back. When Andy Clark and David Chalmers introduced the theory of the extended mind in 1998, they were describing something humans have always done: distributing intelligence beyond the boundaries of the skull. From a stick probing the depth of a river, to a Post-it note on a desk, to the use of the Internet. We have always been natural cyborgs, creatures that extend themselves into the world to expand their possibilities.

This is where the extra-large expectation takes shape. Artificial intelligences do not replicate the human. They generate something new. A well-known example is Move 37, the move with which AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol, the world champion of Go, in 2016. The event was widely interpreted as the definitive surpassing of human capabilities in the most complex strategic game ever created. But if we step away from the logic of competition, Move 37 appears as a different kind of achievement. It was an unprecedented solution, one that a human being, alone, would never have conceived. By traditional standards, it would even have been considered foolish. And yet, thanks to the contribution of AI, it expanded the canon of possibilities in the game of Go.

Moving away from false problems

There is something paradoxical about the age of generative AI. We have access to tools of seemingly limitless power, yet we mostly use them to optimize what already exists: writing emails, creating logos, summarizing documents. There is nothing wrong with that. But we risk convincing ourselves that we have transformed the way we work, when in reality we have only made micro-tasks more efficient. Bullshit jobs, as the anarchist anthropologist David Graeber would put it.

It becomes a race toward numbers that distracts us from what truly matters. If we limit ourselves to analyzing today’s needs, we inevitably fall into this trap. Technology sets the agenda, and we chase applications.

So how do we get out of it? Through a counterintuitive method: the anti-problem. Instead of asking, “How can we use AI to increase productivity?” we flip the question entirely. “What would make AI completely useless for our work? What would be the worst possible way to integrate it into our processes?”

This inversion pushes us to consider that perhaps it is our processes that need to be questioned, rather than generating yet another set of false problems, like those created by a technology in search of applications. Because extra-large expectations, as we have said, are not fantasies about the future. They are emergent properties of the present. And to see them, we need to stop looking where everyone else is looking. And this is how we discover that the worst way to use AI is not to use it too little, but to use it poorly: delegating without verification, automating without understanding, producing without substance. It is a question of expectations. What do we truly expect from AI? And what, in turn, does AI expect from us? It means recognizing that AI has entered our relational space.

Plural intelligences and agentic spaces

As Gino Roncaglia notes in his contribution, today we have access to a plurality of systems with profoundly different natures and purposes: multimodal platforms, deep-thinking models, and advanced research systems. It is a constellation of intelligences operating in increasingly complex and interconnected ways.

We are moving toward what are known as agentic spaces – environments in which AI systems autonomously chain multiple tasks, orchestrate sub-processes, and delegate work to specialized sub-agents. This proliferation raises a daunting question: how are human-AI interactions really changing?

The Anthropic Economic Index, which analyzes millions of conversations with the AI Claude, offers a striking signal. Between December 2024 and August 2025, “directive” conversations – those in which users delegate entire tasks to AI – jumped from 27 percent to 39 percent. This is a turning point that foreshadows what lies ahead: automation has overtaken the once-celebrated idea of augmentation. In other words, people are no longer using AI primarily to explore together or to learn iteratively. Increasingly, they assign a task and expect it to be completed autonomously.

This is where the problem of misaligned expectations emerges. If AI systems are becoming more capable, if automation is accelerating, if companies are investing billions, then why did a recent MIT Media Lab study find that 95 percent of organizations see no measurable return on their AI investments? These numbers do not suggest that AI does not work. They suggest that we are confusing adoption with impact.

This is how workslop is born. The term, coined by researchers affiliated with Stanford and BetterUp Labs, describes AI-generated output that “masquerades as productivity but lacks substance.” Polished slide decks full of jargon and no content. Reports that look professional but require hours of additional work before they become usable.

This phenomenon reveals something essential. Organizations expect AI to boost productivity, yet they send contradictory signals: use it all the time, move fast, delegate everything. The result? People copy and paste without verification, pushing the cognitive burden downstream. This is not AI’s fault. It is the result of poorly calibrated expectations, flawed metrics, and a persistent confusion between adoption and value.

That is why we need what might be called cognitive countermeasures – skills that may soon become foundational. Extended intelligence works only if we know when to trust, when to doubt, when to delegate, and when to retain control. Agentic spaces can become powerful capability multipliers, or factories of workslop. The difference lies in how we design them, and in our willingness to keep responses “incomplete, amendable, and therefore honest,” to paraphrase Matteo Motterlini’s description of the scientific method in Scongeliamo i cervelli, non i ghiacciai (let’s unfreeze minds, not glaciers).

Looking where no one else is looking

There is another perspective we risk missing if we remain locked inside our Western technological bubble. Payal Arora, a digital anthropologist who studies AI in the Global South, shows in her work what happens when artificial intelligence is applied to real problems, with a pragmatism the West could relearn. These examples remind us of something essential. When AI is rooted in specific contexts, when it addresses tangible challenges such as mobility, education, health, and inclusion, it becomes extended intelligence. It creates continuity between different forms of intelligence, or “co-intelligences,” to borrow Ethan Mollick’s term once again.

Extended minds require extended cognitive hygiene

The extra-large expectation for intelligence, then, is a collaborative extension of human thought, one that allows us to become what we have always been: situated intelligences, capable of thinking through others and with others. But this expectation, like all emergent properties in fragmented contexts, does not fulfill itself automatically. It requires what we might call extended cognitive hygiene: learning what to delegate and what to keep internal, how to frame questions that maximize the value of interaction, when to trust and when to doubt.

It requires conscious interaction protocols, as Cabitza reminds us; the ability to look beyond our geographic and cognitive boundaries, as Arora urges; and a clear understanding of the plurality of systems we are dealing with, as Roncaglia explains.